Ethiopia’s civil war continues to spiral into a political and humanitarian crisis and is the latest in a series of internal conflicts. The civil war of 1974 to 1991 saw the Tigray People’s Liberation Front (TPLF) pitted against the military-led dictatorship known as the Derg. At the helm of the TPLF was Meles Zenawi (1955-2012), a strategist and skillful tactician who eventually served as the country’s prime minister from 1995 until his death. Maintaining that power involved corruption, violence, and Western leaders willing to ignore Zenawi’s unsavory enforcement methods in exchange for greater regional stability. Though harrowing and heartbreaking, Ethiopia’s battles are, perhaps, ignored by many Americans, only making headlines when truly atrocious acts trump the everyday horrors we’ve sadly become accustomed to seeing.

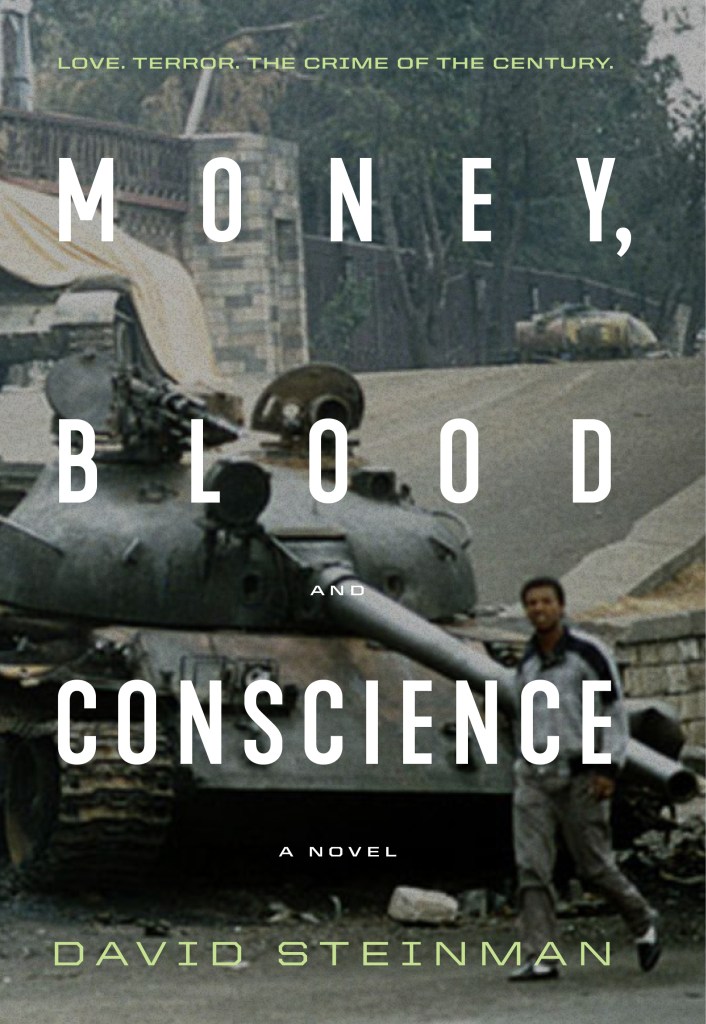

David Steinman’s novel, Money, Blood, and Conscience (Free Planet, 256 pages, $26.95) attempts to shake Western readers out of their stupor by offering a look at the formative years of the man who unapologetically consolidated Ethiopia’s power and influence. Steinman’s Virgil leading us through this inferno is the blissfully oblivious Buddy Schwartz, a Hollywood producer who, in 1986 and on the heels of yet another television success, grows a conscience after watching an ad raising funds for hungry African children. Thus inspired, Buddy launches his own star-studded initiative (think “Live Aid”), which becomes wildly successful. This endeavor puts Buddy in close and regular contact with Zenawi, then the leader of the still-struggling TPLF. Each of Buddy’s visits to Ethiopia reveal fresh acts of violence perpetrated by Zenawi in the name of deposing the Derg, and though Buddy protests weakly, he ultimately continues to provide food and aid to Zenawi in the hopes that those who need help will actually get it–an “ends justify the means” sort of excuse.

To say that the contents of this book are disturbing is an understatement. Steinman is clearly drawing from a deep well of information, having served as a senior foreign advisor to Ethiopia’s democracy movement for over two decades, which leaves this reader wondering if the goal of this effort–to illuminate the unending plight of Ethiopia and the willful ignorance of Western governments–would have been better served if it were a work of nonfiction. To take his Afterword and turn that into a fulsome piece of nonfiction might have been more effective than the narrative devices employed in Money, Blood, and Conscience. Given the severity of the human rights abuses continuing to play out in Ethiopia, there is still time to share those stories and have an effect on those Steinman hopes to influence.