Interview on November 11 2012 at the Waldorf Astoria NYC

Introduction to “Pinocchio” by Umberto Eco, “…it’s not even a fairy tale, since it lacks the fairy tale’s indifference to everyday reality and doesn’t limit itself to one simple basic moral, but rather deals with many.”

On Veteran’s Day a couple weeks ago, the internationally acclaimed children’s book illustrator Fulvio Testa sat down with me over tea in the Peacock Bar at the Waldorf Astoria to talk about his ground-breaking work for Geoffrey Bock’s new translation of Carlo Collodi’s Pinocchio. The wide-ranging conversation inevitably led to a discussion of his artistic philosophy regarding children’s book illustration in general, and how he can’t get New York out of his mind.

Focus and Rhythm

For this project, Testa told me how he created a special storyboard that allowed him to keep constant track of the visual and literary levels he was trying to maintain. During the process, he constantly asked himself, “How can I get readers to understand the story simply by creating an image? There are two ways that I might create an image, either one image with two stories, or one large edited image.” To choose the right scenes for Pinocchio, Testa outlined places where he felt the images would best compliment the text, and read the book repeatedly in order to completely grasp the flow of action. Perhaps equally important to the actual artwork itself, he added, is the pacing and the precise location of where an image is placed in a printed book. “There are fifty-two images in this book, and they are relatively close together. I try to create a rhythm to the illustrations,” meaning that each picture represents a pivotal moment in the story, and in Pinocchio most chapters either end or begin with an illustration. The flowing imagery allows the reader to maintain a steady pace, while creating pauses in the storyline and breaking the text into manageable parts.

Action and movement

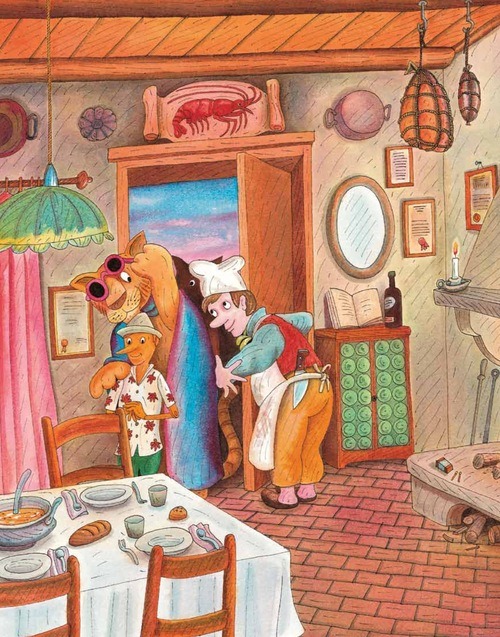

At first glance the art for Pinocchio appears lighthearted and buoyant, however Testa’s work is in reality quite dynamic. To show where the action lies in what appears to be a passive image, Testa pointed to an illustration in the book. In it, Pinocchio stands at Geppetto’s worktable and argues with the Cricket. “Some images are deceptive. They look approachable and friendly, but an older reader will see some of the darker aspects at work here. Look at the table. Pinocchio’s hand is very close to the mallet, which he will pick up shortly and throw at the Cricket, killing him. This is a triangle of violence here.” This is not simply a picture of a quarrel, but a violent avant scène, and yet is still an image that is appropriate for children. “Children need action to convey a story of experience through repetition,” which may be why, in Pinocchio,Testa has filled the pages with the scurrilous puppet in all manner of situations, from skipping school to facing a fearsome serpent. Testa also believes that in order to be successful at his craft, a part of him must retain a childlike understanding and appreciation for the world. “To illustrate, an illustrator needs to have a part of himself that hasn’t grown up yet,” Testa explained. “I have to be willing to re-experience pain, rejection, joy, and other emotions, as if for the first time.”

Fables

Just as parents once used Pinocchio as a way to teach social and moral values, fables are equally important today in constructing a moral compass for children. Testa illustrated an edition of Aesop’s Fables, and finds their universal qualities a captivating way to educate young minds. “Through these stories there is a possibility to acquire a social sensibility.” He views his illustrations as an educational tool because they show how to deal with society from a children’s point of view, which is often more effective than an adult telling a child what is right and what is wrong. There is historical precedent to this approach going back to the nineteenth century, when < em>Pinocchio was first published. Before there was mandatory schooling, children’s books were crucial teaching tools. Carlo Collodi originally published Pinocchio in installments and he initially intended to end the book with the death of the unfortunate puppet. Indeed, the illustration that closes chapter fifteen shows Pinocchio strung up and hanging from a large oak tree. The puppet survives the hanging, and continues on his adventures.

Early Biography

Born in 1947 in Verona, Italy, Fulvio Testa grew up believing he would become an architect. In 1968 he went to Florence, where he enrolled as an architecture student. Testa began traveling extensively throughout Europe in 1970.

Eventually Testa met Štěpán Zavřel, a Czechoslovakian refugee and children’s book illustrator who in 1959 had escaped communism and fled to Italy. Zavrel became Testa’s mentor and advised him to illustrate children’s books. Testa took his advice and discovered that he had a gift for creating images that speak directly to children. In 1971 Testa presented his first work, illustrations for H.C. Andersen’s The Nightingale to a Japanese publisher. The publisher rejected it only because the illustrations were in black ink. The book was published three years later – with colored illustrations. “I have cultivated my reputation [as a children’s book illustrator] since the beginning,” he said. In 1982 he began working with Dial Press, then branched out to other publishing houses. Since the 1970’s Testa has illustrated dozens of books and authored many of his own.

New York

Since 1981 Testa has divided his time between New York City and Verona in six-month intervals. The winter months are spent in his Uptown studio where he works on watercolors and etchings. His time in Italy is devoted to oil painting. “Watercolors require resolute design perspective,” he said, and like many artists, he finds the rhythm of the city to be an excellent inspiration no matter what the subject matter. Oil paintings, like the suite of landscapes he showed recently at the Jill Newhouse Gallery in Manhattan, demand a distinctive focus. “Oil is a different medium. It requires a longer drying process.” Sometimes Testa has ten oils in process simultaneously. Although he paints his dreamy abstract oils in Verona, Testa believes he would never be able to create them if he didn’t live in New York and absorb firsthand the vibrancy of the city that never sleeps.